Fact checking the fact checkers: Debunking AP’s ‘2000 Mules’ hit piece

05/16/2022 / By News Editors

Many of us were alarmed on Election Night 2020 when, while the results were looking good for Donald Trump, multiple states suddenly stopped counting votes. As the night wore on and went into the next day, it seemed that every update was favorable for Biden until he was ultimately named President-Elect.

(Article by Jennifer Van Laar republished from RedState.com)

While Trump’s campaign repeatedly promised to “release the Kraken” and bring forward evidence of election fraud that would prove that the election was stolen, focusing on electronic voting machines, that evidence didn’t materialize. RedState’s Scott Hounsell pointed out various states and cities – even down to the precincts – that should be investigated, and that information was given to the Trump campaign to no avail.

The basis of Hounsell’s “Excuse Me While I Call BS” series was that the supposed results of the 2020 general election were completely incongruent with what had been documented in voter registration data over the preceding four years and with what would be expected given Trump’s performance over Clinton in 2016. For example:

In Pennsylvania, Trump has won every county he won in 2016 except for one, while he picked up another county that Clinton won in 2016. Enthusiasm levels for Biden were lower than they were for Clinton in PA. Since 2016, in the state where Trump won by 45,000 votes, Democrats have lost 48,000 voters while Republicans have added 150,000 voters, outperformed amongst minorities and had record party support and Democrat cross-over vote and yet, Trump only leads by 110,000 voters? BS.

While Hounsell wasn’t able at that time to determine what had happened, it seems that Catherine Engelbrecht and Gregg Phillips of True the Vote have some evidence, in the form of cell phone location data, ballot drop box surveillance video, and more, to suggest that there was a coordinated effort in key states (those in which a small number of votes could swing the state and, therefore, the Electoral College) to illegally “harvest” ballots by paying “mules” to deposit them into drop boxes throughout the given metropolitan area in the month before the election, in numbers that were small enough to fly under the radar on daily counts yet large enough to change the state’s outcome on Election Night. Filmmaker Dinesh D’Souza took this data and interviewed witnesses to create the documentary “2000 Mules,” in collaboration with Salem Media Group, to explain what True the Vote found.

Not surprisingly, by the afternoon of May 4, before “2000 Mules” premiered at Mar-a-Lago that evening, the so-called fact-checkers were out in force attempting to debunk its claims. PolitiFact and Associated Press are the most prominent, and many local rags have run AP’s, magnifying its reach. Of course, the PolitiFact and AP pieces are nearly identical, almost as if they were coordinated. The “facts” or data they use to attempt to discredit D’Souza, True the Vote, and the film are laughably thin — and some are simply not true.

The Associated Press claims that “2000 Mules” did not prove that “at least 2,000 ‘mules’ were paid to illegally collect ballots and deliver them to drop boxes in key swing states ahead of the 2020 presidential election” mainly because the findings are “based on false assumptions about the precision of cellphone tracking data and the reasons that someone might drop off multiple ballots, according to experts,” but the piece lists a few other areas in which they believe the film perpetuated falsehoods.

Let’s go through the various claims AP believes “2000 Mules” got wrong.

Geotracking/Cellphone Location Data

According to Gregg Phillips, True the Vote analyzed more than a petabyte (1,000 terabytes) of data from smartphones in Phoenix, Atlanta, Philadelphia, Detroit, Milwaukee, and Las Vegas, covering the time period from October 1 through Election Day (and through January 6 in Georgia to cover the Senate runoff). In Atlanta, the group says that by using that data they identified 242 “mules” who met their criteria (visited 10 different ballot drop boxes and at least five different nonprofit organizations identified as “stash houses”) during that time frame. Here’s what the AP had to say about that claim:

[E]xperts say cellphone location data, even at its most advanced, can only reliably track a smartphone within a few meters — not close enough to know whether someone actually dropped off a ballot or just walked or drove nearby.

“You could use cellular evidence to say this person was in that area, but to say they were at the ballot box, you’re stretching it a lot,” said Aaron Striegel, a professor of computer science and engineering at the University of Notre Dame. “There’s always a pretty healthy amount of uncertainty that comes with this.”

That’s simply not true. In the first sentence of the quote, the writer says that experts say that a smartphone can be reliably tracked within a few meters. Depending on what “a few” means in this case, that could be six or nine feet. That’s hardly leaving a healthy amount of uncertainty. Also, we’re not just talking about one visit to a ballot box.

Pieces in the Washington Post and the New York Times also characterize cellphone location data as quite specific and reliable. For example, in May 4 WaPo article stoking fear that the Patriarchy could use phone data to determine who got an abortion should abortion become illegal in some states:

Phones can collect precise information about your whereabouts — right down to the building — to power maps and other services. Sometimes, though, the fine print in app privacy policies gives companies the right to sell that information to other companies that can make it available to advertisers, or whoever wants to pay to obtain it.

On Tuesday, Vice’s Motherboard blog reported that for $160, it bought a week’s worth of data from a company called SafeGraph showing where people who visited more than 600 Planned Parenthood clinics came from and where they went afterward.

A 2019 New York Times series, “The Privacy Project,” revealed a lot about how granular this data can be. In a piece from that project titled “Twelve Million Phones, One Dataset, Zero Privacy,” Times journalists reported on what they found after analyzing a data file containing 50 billion location pings from 12 million Americans over a several-month period in 2016 and 2017. In the introduction they state (emphasis mine):

Each piece of information in this file represents the precise location of a single smartphone over [the] period.

And, says the Times, this information isn’t generated solely by big tech or government surveillance, and is openly available to anyone who wants to pay for it.

The data reviewed by Times Opinion didn’t come from a telecom or giant tech company, nor did it come from a governmental surveillance operation. It originated from a location data company, one of dozens quietly collecting precise movements using software slipped onto mobile phone apps. You’ve probably never heard of most of the companies — and yet to anyone who has access to this data, your life is an open book. They can see the places you go every moment of the day, whom you meet with or spend the night with, where you pray, whether you visit a methadone clinic, a psychiatrist’s office or a massage parlor.

In addition, the AP writer says there are many reasons that people might have been close to a ballot drop box on multiple occasions, since they’re placed in high traffic areas like libraries, government buildings, college campuses, that people frequent. That’s definitely true. But are they going to those places regularly late at night or even in the middle of the night? Are they also going to five different nonprofit organizations focused on get-out-the-vote efforts?

In 2021 the Times published a piece titled, “They Stormed the Capitol. Their Apps Tracked Them.” about the January 6 protesters. In that piece they noted that since their 2019 article a new piece of information had become available:

Unlike the data we reviewed in 2019, this new data included a remarkable piece of information: a unique ID for each user that is tied to a smartphone. This made it even easier to find people, since the supposedly anonymous ID could be matched with other databases containing the same ID, allowing us to add real names, addresses, phone numbers, email addresses and other information about smartphone owners in seconds.

The IDs, called mobile advertising identifiers, allow companies to track people across the internet and on apps. They are supposed to be anonymous, and smartphone owners can reset them or disable them entirely. Our findings show the promise of anonymity is a farce. Several companies offer tools to allow anyone with data to match the IDs with other databases.

The data purchased by True the Vote most likely contained the mobile advertising identifier information, which would allow True the Vote to discern the real names, addresses, etc. attached to each potential “mule” device’s owner in seconds, which comes into play with the AP’s next supposed reason that the True the Vote analysis could not possibly be correct:

True the Vote has said it filtered out people whose “pattern of life” before the election season included frequenting nonprofit and drop box locations. But that strategy wouldn’t filter out election workers who spend more time at drop boxes during the election season, cab drivers whose daily paths don’t follow a pattern, or people whose routines recently changed.

It wouldn’t filter them out if the group didn’t also have other information, such as mobile advertising identifiers. But True the Vote has even more than that. For example, the group has chain of custody logs for the ballot drop boxes in question, so they know when election workers visited the drop boxes to collect ballots and can eliminate cell phones at that location at that time from being included in the “mule” category.

Use of Gloves in Georgia Senate Runoff

Investigators found that in the 2020 Georgia Senate runoff, particularly after December 23, 2020, many of the mules seen on surveillance video were wearing blue latex medical gloves when approaching the ballot drop boxes. Gregg Phillips attributes that development to the arrest a day prior of an Arizona woman for ballot fraud, and claims that the FBI used fingerprint data to help catch that perpetrator.

According to the AP, though, the “mules” were just wearing gloves because it was cold out. Because obviously we all wear blue latex medical gloves to keep our hands warm in the winter, then throw them away before getting back to a car or home.

This is pure speculation. It ignores far more likely reasons for glove-wearing in the fall and winter of 2020 — cold weather or COVID-19.

Voting in Georgia’s Jan. 5, 2021, Senate runoff election occurred during some of the coldest weeks of the year in the state, and when COVID-19 was surging. In fact, the AP in 2020 documented multiple examples of COVID-cautious voters wearing latex gloves and other personal protective equipment to vote.

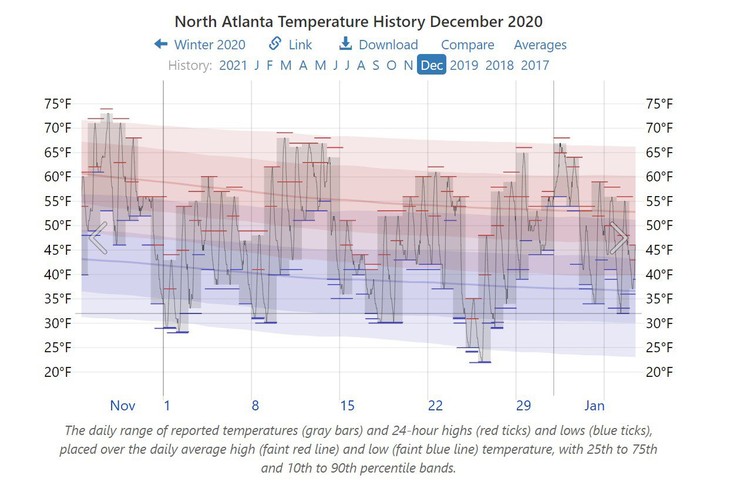

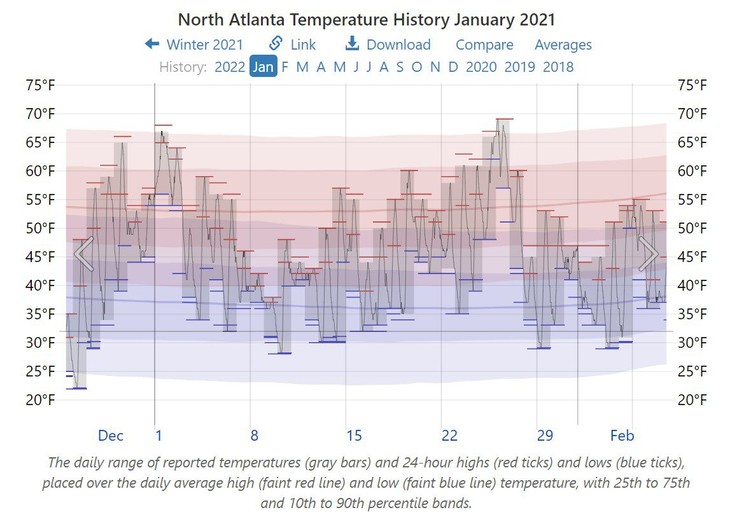

Mail ballot voting for the Georgia Senate runoff began soon after November 18, 2020, when mail ballots went out. The nighttime temperature on December 23, 2020 and through January 5, 2021 weren’t any colder than the weeks prior, and, in fact, between December 29 and January 3, 2021 the low temperature in North Atlanta was warmer than the historical daily average low.

In the movie, this woman is — whose smartphone seems to “live” in South Carolina according to True the Vote, is shown wearing blue latex medical gloves as she deposits multiple ballots in a drop box in Fulton County, Georgia, in December 2020 . . .

. . . then removes them immediately after the ballots are securely in the ballot box and puts them in the adjacent trash can.

It must not be very cold out.

Of course, AP has no comment as to why one would be out in the middle of the night placing numerous ballots in the drop box. I’m sure they will claim that it’s simply a hard-working person who just got off their night shift job and are dutifully taking all of their elderly relatives’ ballots to the drop box. But, of course, that hard-working person also would have visited at least 10 other ballot drop boxes and made five visits to the identified nonprofit organizations alleged to have served as stash houses.

Sounds totally legit.

Photographing Ballots/Ballot Boxes

According to the AP fact check:

In a similarly speculative allegation, the film claims its supposed “mules” took photographs of ballots before they dropped them into drop boxes in order to get paid. But across the U.S., voters frequently take photos of their ballot envelopes before submitting them.

Of the envelopes, possibly. Perhaps one of their individual envelope going into the drop box. Where is the documentation of AP’s claim that U.S. voters “frequently take photos of their ballot envelopes before submitting them”? There is no link back to any story or study documenting that supposed fact. But who takes photos of a stack of ballots? What does that prove for an individual voter? And what good does a picture of the box from a few feet away do if one is trying to prove they deposited their ballot in the box?

Multiple Devices in One Car?

To rebut the movie’s claim that “In Philadelphia alone, True the Vote identified 1,155 “mules” who illegally collected and dropped off ballots for money,” AP noted that True the Vote wasn’t able to obtain surveillance video in Philadelphia and then added a 200-word speculative story from a Pennsylvania lawmaker:

Pennsylvania state Sen. Sharif Street…told the AP he was confident he was counted as several of the group’s 1,155 anonymous “mules,” even though he didn’t deposit anything into a drop box in that time period.

Street said he based his assessment on the fact that he carries a cellphone, a watch with a cellular connection, a tablet with a cellular connection and a mobile hotspot — four devices whose locations can be tracked by private companies. He also said he typically travels with a staffer who carries two devices, bringing the total on his person to six. During the 2020 election season, Street said, he brought those devices on trips to nonprofit offices and drop box rallies. He also drove by one drop box up to seven or eight times a day when traveling between his two political offices.

While his trips to nonprofit offices could meet True the Vote’s criteria for inclusion in the “mule” pool, since we don’t yet know exactly which nonprofit offices in Philadelphia True the Vote was focusing on, we can’t be sure he visited five or more of the targeted nonprofit organizations. And if he did, why? We’re not talking about the Boys & Girls Club here.

In addition, it’s likely that investigators would notice if six devices were traveling together to these various locations then investigate further, and they’d see that the devices were also stopping at legislative buildings and campaign offices. Using the other data, such as mobile advertising identifiers, they’d be able to determine that they belonged to a legislator and not a mule.

The writer should seriously be ashamed that this story — which might or might not have actually occurred — is used in a fact check.

Dropping Off Ballots for Family Members

Knowing how startling and impactful surveillance video of numerous people stuffing a handful (or more) of ballots into the drop boxes would be, it’s important for the legacy media to try to explain that.

Why haven’t the any of the 2,000 mules who committed multiple crimes surrounding widespread ballot trafficking in the 2020 Election been arrested yet?

— Charlie Kirk (@charliekirk11) May 9, 2022

The AP fact check simply declares that “2000 Mules” didn’t properly account for instances in which someone was dropping ballots off at the drop box for family members, and falsely claims that there was no way match up those voters with the cellphone location data True the Vote possessed. The only “proof” AP puts forth to prove their assertion is one anecdote and one instance in Georgia in which surveillance video of one person depositing six ballots into a drop box was investigated and it was determined that the man was depositing ballots for himself and his family:

In some states, in an attempt to bolster its claims, True the Vote also highlighted drop box surveillance footage that showed voters depositing multiple ballots into the boxes. However, there was no way to tell whether those voters were the same people as the ones whose cellphones were anonymously tracked.

For example, Larry Campbell, a voter in Michigan who was not featured in the film, told The Associated Press he legally dropped off six ballots in a local drop box in 2020 — one for himself, his wife, and his four adult children.

Saying that “there was no way to tell whether those voters were the same people as the ones whose cellphones were anonymously tracked” is just laughably incorrect. First, the videos are timestamped, and True the Vote has all of the cellphone data for that location at that time, so they are able to determine the device ID’s for each device at that location at that time. They can also tell where that device was before and after the visit to the ballot drop box. And, using the mobile advertising identifier, they could identify the owner of the phone – and how many family members they have.

We know that True the Vote investigators did look into who the owners of particular devices were, since Phillips mentioned in the movie that the woman in the screenshot above was normally in South Carolina but was a “mule” in Georgia during both the general election and the Senate Runoff.

Some “Mules” Were Also at Antifa Rallies

Here we have another instance in which AP uses speculation as a supposed “gotcha,” but this time they’ve also found a way to insert their political slant into said “gotcha.” To attempt to rebut the claim in the movie that some of the “mules” identified in Georgia were “violent far left actors,” in AP’s words, because their devices “were also geolocated at violent antifa riots in Atlanta in the summer of 2020,” they write:

The anonymized data True the Vote tracked doesn’t explain why someone might have been present at a protest demanding justice for Black deaths at the hands of police officers. The individuals who were tracked there could have been violent rioters, but they also could have been peaceful protesters, police or firefighters responding to the protests, or business owners in the area.

Of course, when AP describes the riots, they’re actually “protests demanding justice for Black deaths at the hands of police officers.” Spare us. And sure, it’s plausible that devices of first responders could be mixed in with the rioters, but business owners? Perhaps, but in my recollection of video footage from the riots, by the time they were getting violent most business owners weren’t anywhere near there. Those who stayed to fight and protect their buildings were the exception, not the rule.

Also, they’re again relying on the “anonymized data” trope to make it seem there is no way True the Vote could have determined who owned the device, or that they didn’t. As described above, they could easily have determined the name and identity of each and every mule. For all we know at this moment, they could have.

It’s clear that the “fact checks” claiming to debunk the content of “2000 Mules” don’t pass muster, and they certainly don’t contain factual information that could be considered in a courtroom — unlike the information presented in the movie.

Read more at: RedState.com

Submit a correction >>

Tagged Under:

2000 Mules, Associated Press, documentary, election fraud, Fact Check, Fact-checking, lies, mainstream media, truth, vote fraud, vote rigging

This article may contain statements that reflect the opinion of the author

RECENT NEWS & ARTICLES

COPYRIGHT © 2017 PENSIONS NEWS